Shimano’s factory is a closely guarded fortress of modernity and manufacturing. Walk inside and you’re greeted with an amazingly spacious, clean lobby with cutaways of their top components for both cycling and fishing. It’s a surface level of finely crafted wood and metal and glass that is the perfect introduction to what is perhaps the cleanest cycling component manufacturing plant we’ve ever visited.

Our tour began, however, well outside their walls, with a well curated tour around Osaka to provide context for what they do.

A Brief History of Metalworking

Shimano was started in 1921 by Shozaburo Shimano, who wanted to create a more reliable freewheel. His father was a metal worker, a craft that has a long history in Japan’s Sakai region, where Shimano is based. (The video above is a quick run through of their Shimano Square concept “store” in Osaka, and there’s a bit that shows one of the original freewheels, a very rare and hard to find item these days. It also shows closeup details of the exploded-view components you’ll see in photos below.)

Here, steel was imported to build tools 1,600 years ago in order to build the tombs for their emperors. Digging and cutting tools allowed them to create trenches and giant burial mounds more efficiently, as well as cut stone. The largest such mound is the Nintoku-tenno-ryu Kofun, which is part of the Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group in Osaka. It measures 486m long with a series of three moats around it. The dirt pulled up to create the moats was piled up to create the keyhole shaped burial mound, which was then covered with neatly arranged stones to prevent erosion. Built in the early 5th century, it has since overgrown with trees

Over time, iron forgers began crafting Samurai swords for generations, as well as armor and helmets. As the warrior class system fell away and carrying a sword on the streets became illegal, the bladesmiths switched to making knives.

In 1553, the Portuguese introduced guns to Japan, who then used their expertise to perfect the Match Lock type of rifle and, eventually, bicycle frame repair and manufacturing. More than a millineum of metal working has progressed to all manner of forging, and that’s where Shimano comes in. Based in Osaka, this history and culture becomes evident as we tour their factory.

It Starts with Forming

Shimano’s campus takes up several city blocks and continues to grow. Raw material arrives in the form of sheets and rods of metal, then goes first to the forming room. Once cut to size, sheet metal is pressed into cassette cogs. Modern 11-speed cogs are stamped into shape over multiple steps to reach their final shape with all of the holes. This multi-step process shapes the metal slowly to so it won’t crack. The finished product is 1.6mm thick with tooth profiles narrowed to just 0.2mm thick at their edges…with a tolerance of just 3 micrometers!

They stamp the titanium cogs here, too, but they take more pressure to cut, so the internal dies and parts have to be swapped out when switching materials.

Alloy blocks are cut into blanks, which are then stamped into shape in a cold forging process they’ve been perfecting since 1962. The largest machine produces up to 2,000 tons of pressure. Each arm takes several steps to reach its final shape, it can’t just go from blank to finished arm in a single press.

Two-piece arms, like the higher end Dura-Ace, Ultegra, XTR, XT, etc., use a blend of hot and cold forging. The front of the arm is cold forged, and the rear is heat forged at 500ºC after spending anywhere from 30-60 minutes being warmed up to soften the metal. Once complete, they two pieces are bonded together.

They turn out a few thousand crank arms per day, usually batching different models throughout the day. Shimano operates other facilities off site, too, but they produce most of the parts for XT, Saint, SLX, Ultegra and 105 here. XTR and Dura-Ace are 100% made at this plant. They produce more cassettes than cranks, partly because they’re a higher wear item, but also because not everyone specs a complete Shimano group, but Shimano cassettes are almost always included.

The lever bodies, if they’re made of metal, are die-cast. This is another process they’ve refined over the years, reducing the number of parts in the mold to simplify it without requiring additional post-production machining.

Rim brake arms start life as solid aluminum coil before being forged into shape. Why so much forging? Because it maintains the inherent crystal structure of the metal, which results in a stronger, more resilient piece.

Disc brake calipers are “hot closed die forged”, not die-cast or machined, to get their basic shape. Shimano uses high frequency induction heating to speed up the process, and it yields a nearly complete part in a single step, which is how they get such a smooth one-piece caliper. The process allows them to get more complex shapes than they could with forging, and is more appropriate for certain materials (like magnesium). The internal cavity is then machined out to create the piston bores, etc. Which brings us to…

Machining means Milling, Turning & Broaching

After forging, parts are brought to the machine room to be finished, bringing them within required tolerances. In particular, the cranks receive plenty of attention to ensure the inner and outer faces will be perfectly fitted to one another. And chainrings need to mate with those with zero play, and the hole where it slides into the spindle must also be perfectly aligned.

Different lines machine different parts, but the same workers oversee the process for cogs, cranks and derailleur parts, as well as fishing equipment. It all gets finishing work done here.

Adjacent to the machining room, a process control room monitors the entire factory, from each individual machine’s performance to air quality to sound levels and more. If a machine is acting weird, they can message its operator to inspect it.

Surface Treatments

This particular area was closed to our tour because it’s where they suffered a fire in early 2018. It’s still being repaired, but also, probably not nearly as exciting as how the parts are actually made.

Parts are heat treated before machining to add rigidity, hardness and flexibility. Those may seem like opposing characteristics, but think back to the virtues of Japan’s legendary knives and swords. They must be hard to retain their edge, but flexible so they don’t break upon impact. Steel, titanium and aluminum – they all get it.

Bonding

Once the parts are treated and machined, a fully automated system of computer controlled robots applies the glue and bonds together the crank arms, hollow chainrings, calipers and other parts. This process lets them use longer, larger hollow sections to save more weight than they could with a one-piece hollow forging.

If you pull up that date code sticker on the back of your cranks (or just press firmly on it to feel underneath) you’ll find a small screw. This closes the hole used to suck air out of the hollow section during bonding, helping to pull glue into all of the nooks and crannies for a completely sealed bond. It’s not a vacuum, but it gets the job done.

Once the parts are pressed together in a jig, they go into the oven. Shimano won’t disclose baking time or temp. The bonding agent is their own formula they worked with the glue manufacturer to develop.

Once out of the oven, the excess glue that squeezes out is machined off, then they go back to the finishing room for final anodizations and surface treatments.

Around the House

The home where Shozaburo Shimano first created that freewheel has been relocated to a very posh part of town, across the street from the moats surrounding the Nintoku-tenno-ryu Kofun. It now serves as a meeting place, somewhere offsite to take visitors and business partners for a lunch or casual talk.

Its upkeep is pristine, inside and out, with beautiful gardens, manicured trees and perfect paths surrounding it. Inside is a showcase of Japanese minimalism, and an homage to the homes of the era. Paper walls let them transform the space to meet their needs, creating privacy or large party rooms, while letting light fall through. Windows are on the lower half of the walls and doors because they sat on the floor, not up in chairs and couches.

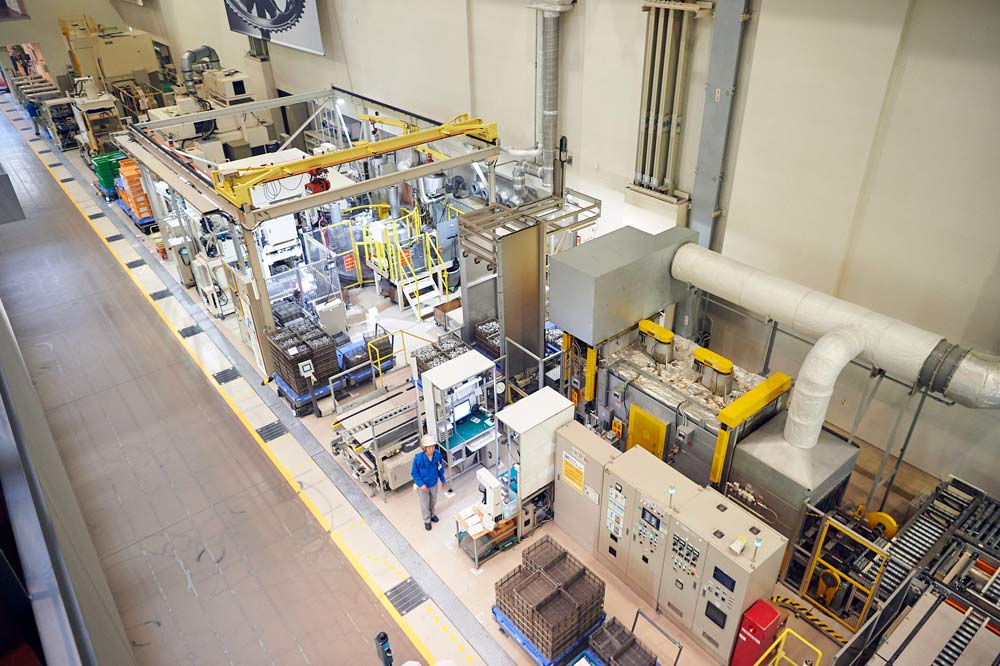

Back at Shimano’s headquarters, the clean aesthetic remains. High end wood decking runs throughout, inside and out, joining upper level rooms and providing a bird’s eye view of the forging machinery.

On the roof is a massive garden, broken into rows by skylights. Elsewhere, reflectors bring light into lower levels through a system of tubes and mirrors, reducing their energy needs.

Employee parking provides spots for 1,000 bicycles in multiple locations. This room holds up to 543 bikes, and they say they can fit 13 bikes in the space it would take to park one car. Up to 40% of their employees bike to work thanks to incentives that pay them for commuting.

Around the factory, driverless robotic forklifts shuttle raw materials and parts where they’re needed, pulling from an automated warehouse with robotic platforms keeping everything where it needs to be.

All photos from inside the factory are courtesy of Shimano. We were allowed to direct the photographer, but not bring our own cameras or phones into the building. While they were very accommodating and answered any questions we had, any photos needed to be screened in advance. Which is normal for such places, few companies will open up to any photo from any angle. Here, it’s in large part because they have some new things coming…

Huge thanks to Shimano for the hospitality and opportunity. Stay tuned to Bikerumor on Friday for more news!